The Karoo – a vast semi-arid region in the heart of South Africa – is not usually the first place that springs to mind when thinking about elephants. The unmistakable pachyderms are typically associated in the popular mindset with lush savannahs and vast, fertile grasslands – where they once roamed in herds said to have been hundreds strong.

However, historical records indicate that centuries ago these adaptable mammals also explored vast swathes of more arid landscapes like the Karoo, and growing research is showing the ecological importance of reintroduced populations to ecosystems in the Karoo region.

As part of Samara Karoo Reserve’s commitment to reintroducing historically-occurring wildlife, in 2017 a population of these mega-herbivores was established on the reserve, located in the Camdeboo region of the Eastern Karoo, after an absence of approximately 150 years.

This milestone reintroduction was not just a win for conservation of a species whose population on the African continent has plummeted in recent years – it has also provided an opportunity to explore why elephants belong in the Karoo, and how reintroducing them to the landscape could be key to ensuring ecosystem resilience into the future.

In the footsteps of giants

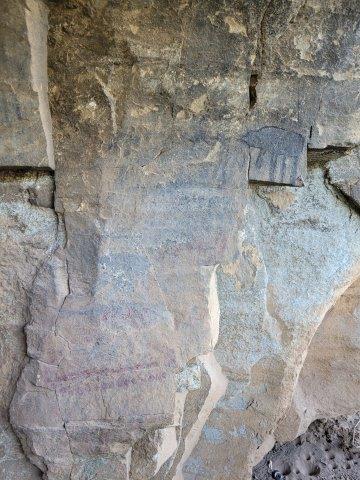

The late CJ Skead was an Eastern Cape naturalist who put together a compendium of historical records of mammal distribution within the province, including elephants. His work forms the basis of current understanding that, several centuries ago, elephants travelled deep into the heart of South Africa’s Eastern Karoo region. Although sight records are scarce, many reliable palaeontological records (including bones, tusks and teeth) have been discovered in the area, including a tusk embedded in a dry riverbed on Samara itself. Skead believed that the absence of written elephant sightings in the region may reflect early eradication of elephants by hunters equipped with firearms, before literate observers could document them. There are clues to their presence in the rock art of the San people too – a cave shelter on Samara, most celebrated for its painting of a cheetah, also contains paintings that experts believe depict elephants. Whilst elephant presence in the more inhospitable parts of the Karoo is thought to have been transitory, the densely-vegetated and water-rich habitat along the base of escarpments, including those at Samara, are deemed likely to have provided habitat islands for resident populations. Indeed, several elephant populations across Africa exist in far drier areas than the Eastern Karoo. The so-called desert elephants of Namibia’s Kunene region experience an average annual rainfall of less than 100mm, compared to the 350mm average annual rainfall of the Camdeboo Karoo, in which Samara sits. In times of drought, resourceful elephants have been known to use their feet and trunks to dig for water in dry riverbeds.

Elephants as ecosystem engineers

Elephants are well-known as ecosystem engineers – creating and perpetuating new habitats and ecosystem processes through physically changing the environment they live in. As a result of their sheer size and power, this is unsurprising! The ways in which elephants shape their ecosystems may also enable other species to survive. These benefits include making vegetation accessible to smaller browsers, creating micro-habitats for small mammals and birds and ultimately supporting certain predator numbers by encouraging the maintenance of the grassland on which their grazing prey depends. An absence of elephants has consequences too – scientists refer to the phenomenon of “mega-herbivore release”, suggesting that current vegetation structures in existing Karoo landscapes reflect the centuries-long absence of elephants from the region. Plant and animal communities which have been protected from elephant browsing for such a long time-period may have developed differently as a result of this sizeable absence. In this manner, the impacts that elephants have on vegetation may represent a restoration, rather than a degradation, of ecological processes.

This is relevant not only to ongoing monitoring of elephant impacts in Karoo landscapes, but also to attempts to restore degraded habitats, especially subtropical thicket which is present across much of the Eastern Karoo. Elephants have been called the “conservators of thicket” as, put simplistically, they tend to feed from the top of the tree canopy down, unlike domestic livestock which tend to feed from the bottom up, hindering the continued recruitment of plants and resulting in the die-back of species like Spekboom. The key message is that it is wild, indigenous species that are best placed to help maintain resilient ecosystems as they have co-evolved with the vegetation over time.

8 years of monitoring

Since Samara’s elephant reintroduction in 2017, the movements of the elephants and their impacts on the vegetation of the reserve have been monitored by the conservation team, guided by Samara’s mandate of managing the landscape for biodiversity impacts and ecological processes.

The monitoring has revealed some interesting insights:

- In the southern part of the reserve, the toppling of many short-lived, fast-growing sweet thorn trees (Vachellia karroo) has promoted the growth of grasses, created micro-habitats and provided new food sources for a variety of smaller species.

- Elephants have been recorded feeding on alien invasive vegetation such as pepper trees (Schinus molle), with several bulls having been seen knocking down large, mature pepper trees – an important land rehabilitation function within riverine systems where invasive trees are prevalent and almost impossible to eradicate by hand.

- The way in which elephants harvest Spekboom branches (Portulacaria afra) is being explored as an alternative planting method as part of the reserve’s Spekboom project. Traditionally, cuttings are placed vertically in the soil to root from a single node. Elephants on the other hand tear off small branches of Spekboom, chew them and drop them on the ground where they land horizontally with many possible nodes from which to reroot in the soil.

Research from similar landscapes has also informed Samara’s approach to elephant management. One such study, conducted in a section of the Addo Elephant National Park that sits within the Karoo biome, revealed that the jacket-plum trees (Pappea capensis) being knocked over by elephants had on average 14 new seedlings growing on the site of each toppled tree, even during drought periods. The new trees also took on a different shape as they grew – a dense shrub shape rather than the typical umbrella shape often seen on the landscape. This meant that forage was more readily available to smaller browsers. Perhaps not as pleasing to the human eye, but more beneficial to the biodiversity on the landscape.

Scale is key

It goes without saying that giants need space. In small, fenced-in areas of excessively high elephant density the impact of elephants can be highly destructive to vegetation and other animals alike. This is why Samara is working with local stakeholders to create a much larger protected area in the region for wildlife to thrive. The ambition is to link together the Addo Elephant National Park, Camdeboo National Park and Mountain Zebra National Park through ecological corridors which enable the migration of animals including elephants. With emerging science on the importance of rewilding landscapes for carbon sequestration, the provision of ecosystem services and the protection of biodiversity, this would provide a winning plan for the people and wild places of the Karoo.

Samara Karoo Reserve is a leading conservation journey to restore 67,000 acres of South Africa’s Great Karoo landscape and beyond through rewilding and responsible tourism. Staying at one of Samara’s lodges acts as a direct contribution to this vision.